Like many founders, product managers, and all around builders, I’m certain you’ve either come across or had the book “The Cold Start Problem” by Andrew Chen recommended to you. Seemingly hailed as a proverbial “source of truth” for builders, entrepreneurs, and product leaders, I figured I should jump into this read as an intro to understanding product adoption and rapid scaling. Chen takes the broad “this product was able to scale due to network effects” and deep dives it methodically, by focusing on what he describes as the core 5 stages of a network growth, leading to initial user acquisition and growth. Transparent moment: Prior to reading, I had no scientific understanding of what Network effects were. My understanding was pretty pedestrian as a user of several products that historically scaled quickly. I had never thought deeply about the value proposition behind these products and how it came to be realized by so many users so quickly.

Generally speaking, a network effect is the reaction to a product that has adopted a significant amount of users, increasing in intrinsic value as the number of users increase. In other words, the network itself emits value to the user base. Think about how the value of Instagram, or Slack (both, real anecdotal examples used in the book) would materially decrease, if none of your friends, family, and coworkers were using them. “Come for the tool, Stay for the network” comes to mind when builders are considering developing sustainable products (more on this later). How do builders balance the consideration of what target users may value upfront for the purposes of scaling against the values that are sustainable in the long term?

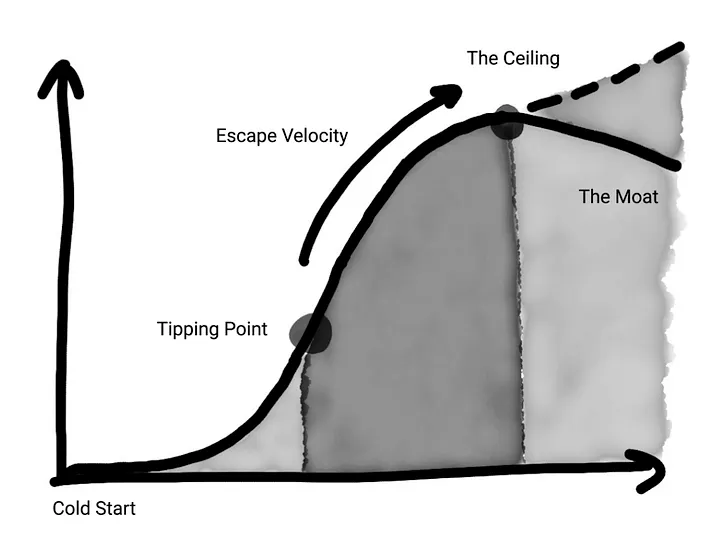

Chen breaks down the network growth cycle using the following phases:

1.The Cold Start problem

For most, this is likely the most critical phase in their product cycle, as this is where product market fit is put to the test. This phase encapsulates the “how to get to the smallest possible network that can sustain and grow on its own” idea. For your product offering, is the solution relatively easy to engage with? Does it specifically solve a pain point for users? If so, starting with an “atomic network” comes highly recommended, in this read. I think the ability to leverage a small group of users is important here for product owners, as the atomic network presents an opportunity to create feedback mechanisms that can feed into ongoing product development as your product scales.

2. The Tipping Point:

The phase follows a successful, and functional atomic network, now the challenge is to replicate that network over and over again (scale). Chen provides several anecdotes to help understand this phase more — For Tinder, and Uber for examples, this replication was done on a city basis. For product owners, this replication COULD be based on personas, for example, or the jobs to be done framework. The main takeaway here using replication and repeat to create a larger ecosystem (at some point several atomic networks will connect) .

3. Escape velocity:

This is the phase where products battle against inertia, and scaling becomes paramount. The momentum from the tipping point needs to be capitalized, and user growth should begin to occur “naturally”, aka “going viral”. The notable part of this phase is the expected reduction in customer acquisition cost(CAC), thus better unit economics. Users demonstrate high engagement as the app becomes more valuable with more users.

4. Hitting the ceiling:

You guessed it, this is typically where product growth begins to stale. Competition, replacements, overcrowding, might all act as contributors to the product plateauing. For product owners, this is where thinking about adjacent markets, and or even brand extensions might play well. New regions & new services are other outlets to look to in order to continue growth.

5. The Moat:

Network based competition has its advantages, but certainly its challenges. One being that the strategy of building and sustaining (attempting to) network effects is not unique. Competitors are likely doing the same. Developing a defensible moat around your product/business, is critical in order to thwart competition. At some point, the product’s moat is its brand, and reputation. Competitors may be able to replicate features while replicating a network is much more difficult. The dynamics for heavily networked offerings skew to a “winner-take-all” environment.

Chen does a great job at introducing frameworks backed by several relatable anecdotes and metrics. Chen does this well by invoking examples such as Facebook, Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, Slack, Instagram, Reddit, TikTok, YouTube, Twitter and more. The brilliance in this is that many readers can relate as users of this products, and have likely consumed these product offerings across multiple phases. “The ability to attract new users, or to become stickier, or to monetize, become even stronger as its network grows larger,” Chen states.

It’s certainly worth a read, but I want to callout the biggest takeaway.

Biggest takeaway:

Builders should zero in on “The Hard Side” of a network — the small percentage of people that typically end up doing the scarce (and most valuable) part of the community. Scaling the hard side of a network is often what accelerates network growth for most products. This could mean attracting content creators to a new video platform, or sellers to a new marketplace, or the project managers inside a company to a new workplace app. The other side of the network will follow. This again goes back to the notion that the product should be built with an important value offering, and it should address “the Hard Side”.

Conclusion:

You cannot exist in business today, and not have heard the term “network effects”, citing its wildly loose use and misunderstanding. Chen did note that network effects can be limited and may only go so far. However, this read didn’t go far enough, as the anecdotes raised on the issue were all mainly environmental (Uber exiting China). I was also expecting more in the “Hitting the Ceiling” and “Moat” sections considering this is where things get really ambigious for existing platforms. This doesnt take away from the strong earlier sections in this book around developing the “atomic network”, and replicating. I’d highly recommend Chen’s book. If you’re working on starting or growing a company that relies on networks, it’s a must-read.